-

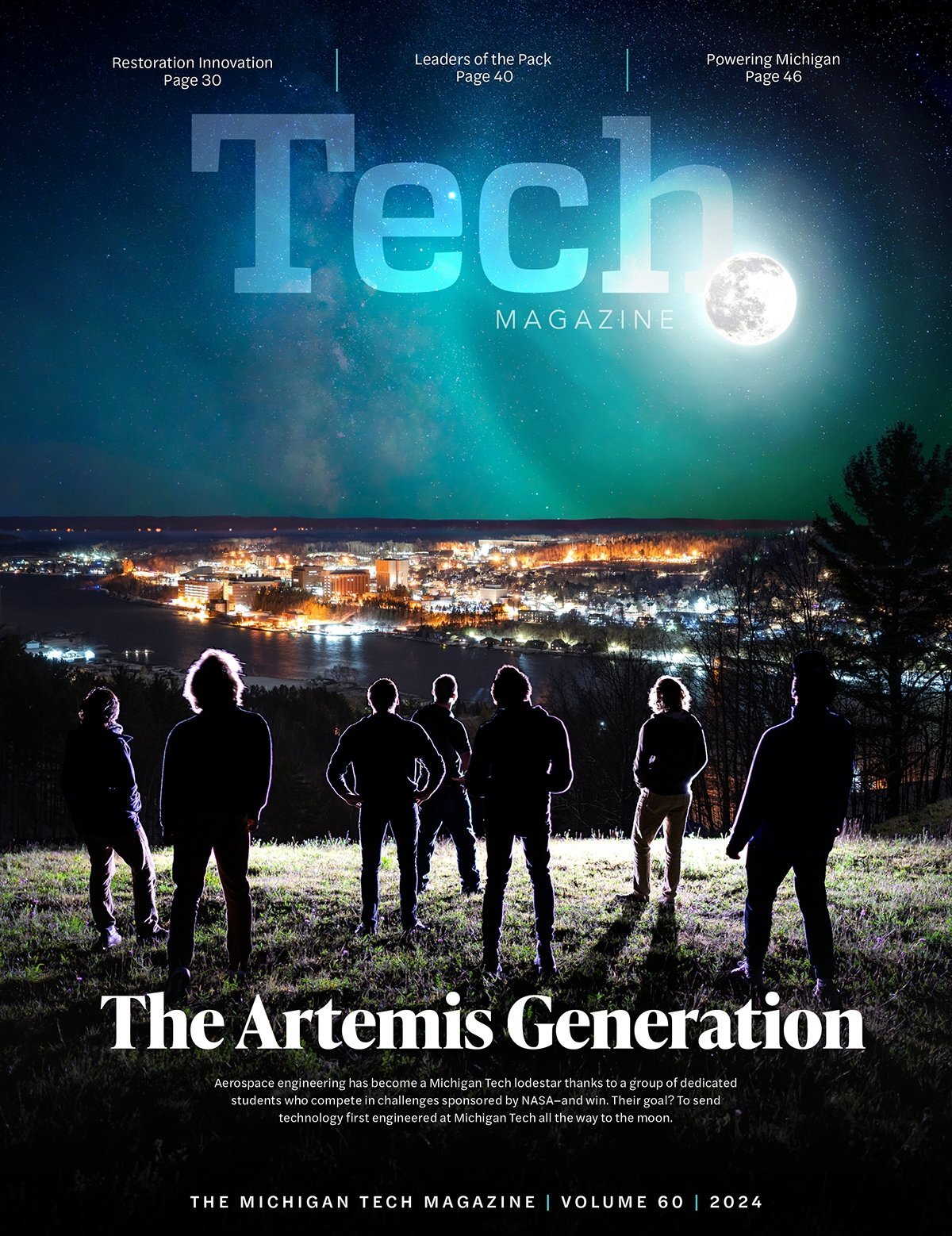

The Artemis Generation

Michigan Tech's Planetary Surface Technology Development Lab is making a name for itself in the aerospace industry with innovative ideas and engineering prowess. We shadowed the PSTDL team for a year to learn the secrets of their success. It's 5:58 p.m.—two minutes to game time—and the Flat Moon Society is only just beginning to show signs of panic. Team captain Travis Wavrunek '20 '21 '24 scans the snow-covered Walker Lawn anxiously, looking for the team's regular goalie, Chuck Carey '22 '23, who is clearly running late. Other Society members huddle to revise their positioning and strategy. The referee blows the whistle, summoning players to the ice. The expression on Travis's face shifts from anxiety to resignation. Despite being one of the team's top scorers, he will have to fill in as goalie until Chuck arrives.

-

Leaders of the Pack

-

Powering Michigan: Michigan Tech Alumni Lead the Energy Industry Transformation

-

» Interdisciplinary

Research In Focus

-

» Interdisciplinary

Research in Focus: Team Science—Putting People First

-

» Interdisciplinary

Research in Focus: H-STEM Rising

-

Research in Focus: Shedding Snow, Powering UP

-

» Interdisciplinary

Research in Focus: Needles, Haystacks, and Sugar Chains

-

Q&A With Chemical Kim

-

» Interdisciplinary

1400 Townsend Drive

-

Dream Jobs: Chicken Tramper Ultralight Gear

-

Alumni Engagement

On the cover: Aerospace engineering has become a Michigan Tech lodestar thanks to a group of dedicated students who compete in challenges sponsored by NASA—and win. Their goal? To send technology first engineered at Michigan Tech all the way to the moon.

Planetary Surface Technology Development Lab members on top of Mont Ripley. Composite photo by Kaden Staley.

Published by University Marketing and Communications

- Editor

Rick White - Assistant Editor

Jessie Tobias - Writers

Wes Frahm

Calvin Larson '10

Cyndi Perkins '22

Stefanie Sidortsova - Designers

Bob Gross

Jen Withers - Photographer

Kaden Staley - Student Photographers

Daniel Staelgraeve '26

Conlan Houston '26 - Videographer

Ben Jaszczak '15 - Production Manager

Jodi Miller - Social Media Manager

Haley Goodreau - Web Editor

Megan Ross '00 - Contributors

Kevin Fales, Katalin Fodor, Ronaldo Lopez, Jen A. Miller, Tristan Spinski, Carinn Tryon '25 - Executive Editors

- Allison Carter '95, Executive Director of Marketing, University Marketing and Communications

- Natasha Chopp '06 '15 '17, Director of Research Operations and Faculty Liaison

- Rick Koubek, President

- John Lehman, Vice President for University Relations and Enrollment

- Jennifer Lucas ’09, Assistant Vice President of Alumni Engagement

- Dave Reed, Vice President for Research

- Ian Repp, Associate Vice President for University Marketing and Communications

- Bill Roberts, Vice President for Advancement and Alumni Engagement

- Comments to the editor:

magazine@mtu.edu - Research questions:

research@mtu.edu - Alumni inquiries and mailing address changes

alumni@mtu.edu