Entomologist Thomas Werner has studied fruit flies from coast to coast. But his rarest discovery to date was close to home.

Armed with a banana-baited live trap and a strong desire to disprove a gap in a species distribution map, the Michigan Technological University professor of genetics and developmental biology found a single specimen of the species Drosophila narragansett on the Maasto Hiihto public recreation trail in Hancock, Michigan.

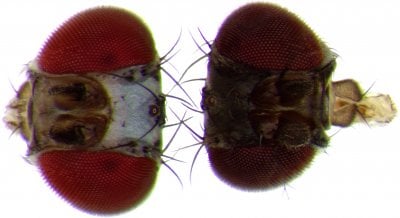

Researchers suspected that Drosophila narragansett, a silver-faced fruit fly, was extinct. "Astonishingly, it seems not to have been collected within the past 60 years despite its broad range," said Werner.

The investigation that led to the elusive fruit fly was entirely unplanned. It started with an irresistible research paper in the hands of Werner, an educator who has been raising awareness about the scope and importance of fruit flies throughout his career.

He has co-authored two volumes of the Encyclopedia of North American Drosophilids. Volume one covers fruit flies of the Midwest and Northeast. Volume two lists species of the Southeast. His co-authors are John Jaenike, a professor emeritus of biology at the University of Rochester, and former student Tessa Steenwinkel. Steenwinkel, a 2020 MTU graduate in biochemistry and molecular biology, earned her master's in biological sciences at Tech in 2021. She is now a development, disease models and therapeutics graduate student at Baylor College of Medicine.

Mysterious Map Sets Professor on the Hunt

Because he's one of a very few experts on fruit fly identification, research papers submitted for peer review frequently come Werner's way. He was on Christmas vacation with family in Mexico in 2023 — definitely not planning on reading research papers — when an emailed request caught his attention.

But Why Do Fruit Flies Matter?

As Werner will attest, fruit flies are more than kitchen pests. They're miniscule genomic models that offer a mirror into the causes of human conditions.

"Fruit fly research relates to chemotherapy and cancer studies, metabolic disorders — some fruit flies are resistant to mushroom poisons. It's all relevant," he said.

"Just the one fruit fly species found in the kitchen can be used to study almost all human diseases."

Werner is referring to Drosophila melanogaster, the species humans most commonly encounter because it's drawn in by our rotting food. The tiny and relentless composters are one of at least 350 known fruit fly species on the North American mainland. Werner is cataloging them all.

"I thought, 'Oh gosh, I don't want to review a long paper right now," said Werner. "But then I looked at it and saw it was from David Grimaldi, from the American Museum for Natural History in New York. He's a great guy who writes about all the weird fruit flies that people don't get to see. All the understudied species."

Grimaldi's latest paper focused on the Drosophila affinis species group. "These are the little black fruit flies. Some in this group are very common. Some are not so common," said Werner. He'd just spent a year reviewing the group for his third book, covering fruit flies of the Northwest, slated for publication next year. After reading about two thousand scholarly papers on the group, he felt he couldn't say no to the review.

Werner resolved to read the paper when he was home from vacation. But he couldn't stop himself from taking a peek. "I started reading the first couple of sentences and I just plowed through this whole thing the whole night, reading it on my phone. It was so interesting. I was so drawn into it. I just couldn't not read it, and I was like, 'Oh my gosh, I have all these ideas!' It was like 'Whoa, this is the nicest paper I've ever read!'"

Werner was especially intrigued by a hand-drawn species distribution map included as a figure in the paper. It showed a zone of exclusion for two common fruit flies encompassing a relatively small area just shy of his backyard in the Keweenaw Peninsula, home to Michigan Tech in the state's Upper Peninsula. What's more, Werner had seen the species in the Huron Mountains, about 50 miles east of Keweenaw, where he cataloged 35 species of fruit flies. The no-fly zone didn't make sense.

"I wondered why anyone would draw the line below here for this common species," said Werner.

This summer, he planned a leisurely trip north into the exclusion zone, hanging fly traps baited with bananas to prove the species was present. "It was just like a little thing, just to prove my point," said Werner, who doesn't normally research so close to home because he's familiar with all the local species. Or so he thought. He never expected that his casual experiment would yield a rare species. And he didn't notice anything different about the two flies he captured until he went back to the lab, administered ether to put them to sleep and followed his impulse to look them in the eye.

"Drosophila narragansett and the super common Drosophila athabasca look exactly the same, except when you lift them up to look at them face-on," Werner explained. "My inner voice is often right. It said, 'Look at their faces.'"

Ethalyzed fruit flies sleep on their sides. Manipulating the tiny insects to get a full facial view is difficult.

"You have to carefully lift them up and turn them so that you see straight in the face," Werner explained. "You have to go up with the focus to see. And the first face was silver. And I thought, 'No, no, that cannot be. That cannot be.'"

Wondering if he was hallucinating, Werner looked at the second fly, whose face was black. The contrast was clear. "I was in a cold sweat," Werner said. "They started waking up. I put them away. I started texting my collaborator John, in Rochester, New York, who co-authored the books with me and Tessa."

Jaenike, a professor emeritus of biology at the University of Rochester, specializes in evolutionary ecology and is well known for his research on fruit flies. The researcher had an unconfirmed Drosophila narragansett specimen show up in his front-yard compost bin seven years earlier. During shipping to the Werner lab for imaging, the specimen's face fell into a preservative that turned it black. Jaenike's lab was able to produce a partial genetic sequence from the remains. "It was 97% close but not entirely clear," said Werner.

Werner's find is now the first specimen of the species to be completely sequenced. "My collaborator Bernard Kim, who works in Dmitri Petrov's lab at Stanford University, recently confirmed its identity. It is indeed Drosophila narragansett!" he said.

Fruit Fly Documentation and Discoveries Continue

Drosophila narragansett is not Werner's first rare find. He previously discovered a fruit fly species, Amiota tessae, which he named for his graduate student mentee Steenwinkel.

The potential for other unique finds awaits. For three years, Werner has been taking his lab on the road each summer in order to document fruit flies across North America. "It's just like being in the home lab," Werner said. "Except the air is fresher."

The experience has transformed the way Werner pursues his research. "I want to be able to spend part of my time doing fieldwork and part of my time doing lab work. I find a lot of joy in both of those activities," said the award-winning educator, who revels in sharing his knowledge with his students at Tech and elsewhere. "It has changed the way I do science."

Werner has been collaborating with Kim on genomic sequencing of fruit fly species since the two met in 2020 on Zoom. At the time, Kim was a new postdoctoral researcher in the Petrov Lab at Stanford and reached out for help. Kim joined Werner this past summer on the Pacific Northwest fieldwork for the encyclopedia's third volume. So did Stanford graduate student Daniel Shaykevich, who is working on a documentary about the expedition.

Werner had not studied the local fruit fly population in his hometown for years. But he plans to go back to the trails next summer.

He thinks timing may be part of the reason the believed-to-be-extinct fruit flies could not be found. Early summer is not the most active period for fruit flies in the region. "August is the time when our produce baskets become a magnet," said Werner.

His traveling lab is likely to progress much farther afield.

"There are another thousand fruit fly species on the Hawaiian islands alone," said Werner. "That may be next on my list."

Michigan Technological University is an R1 public research university founded in 1885 in Houghton, and is home to nearly 7,500 students from more than 60 countries around the world. Consistently ranked among the best universities in the country for return on investment, Michigan's flagship technological university offers more than 120 undergraduate and graduate degree programs in science and technology, engineering, computing, forestry, business, health professions, humanities, mathematics, social sciences, and the arts. The rural campus is situated just miles from Lake Superior in Michigan's Upper Peninsula, offering year-round opportunities for outdoor adventure.

Comments