-

» Interdisciplinary

R1: Research in Focus

Michigan Technological University has officially joined the ranks of R1 research institutions—a milestone that reflects decades of impactful work and affirms the University’s standing as a leader in addressing critical challenges. Michigan Tech joins Wayne State University, Michigan State University, and the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor as the fourth R1 institution in the state, further contributing to Michigan’s dynamic research ecosystem. Michigan Tech has been welcomed as the newest R1 university in the University Research Corridor (URC), an alliance of Michigan’s leading research institutions that drives economic growth and revitalization in the state and fosters research innovation.

-

» Interdisciplinary

Paving the Way for Energy-efficient Transportation

-

Modern Mining’s Moment

-

Charting New Waters in Great Lakes Mapping

-

Finding the Balance

-

Engineering the Elements

-

The Scent of Success

-

Q&A with Korey Kiepert

-

» Interdisciplinary

1400 Townsend Drive

-

Dream Jobs: Shaggy’s Skis

-

Alumni Reunion

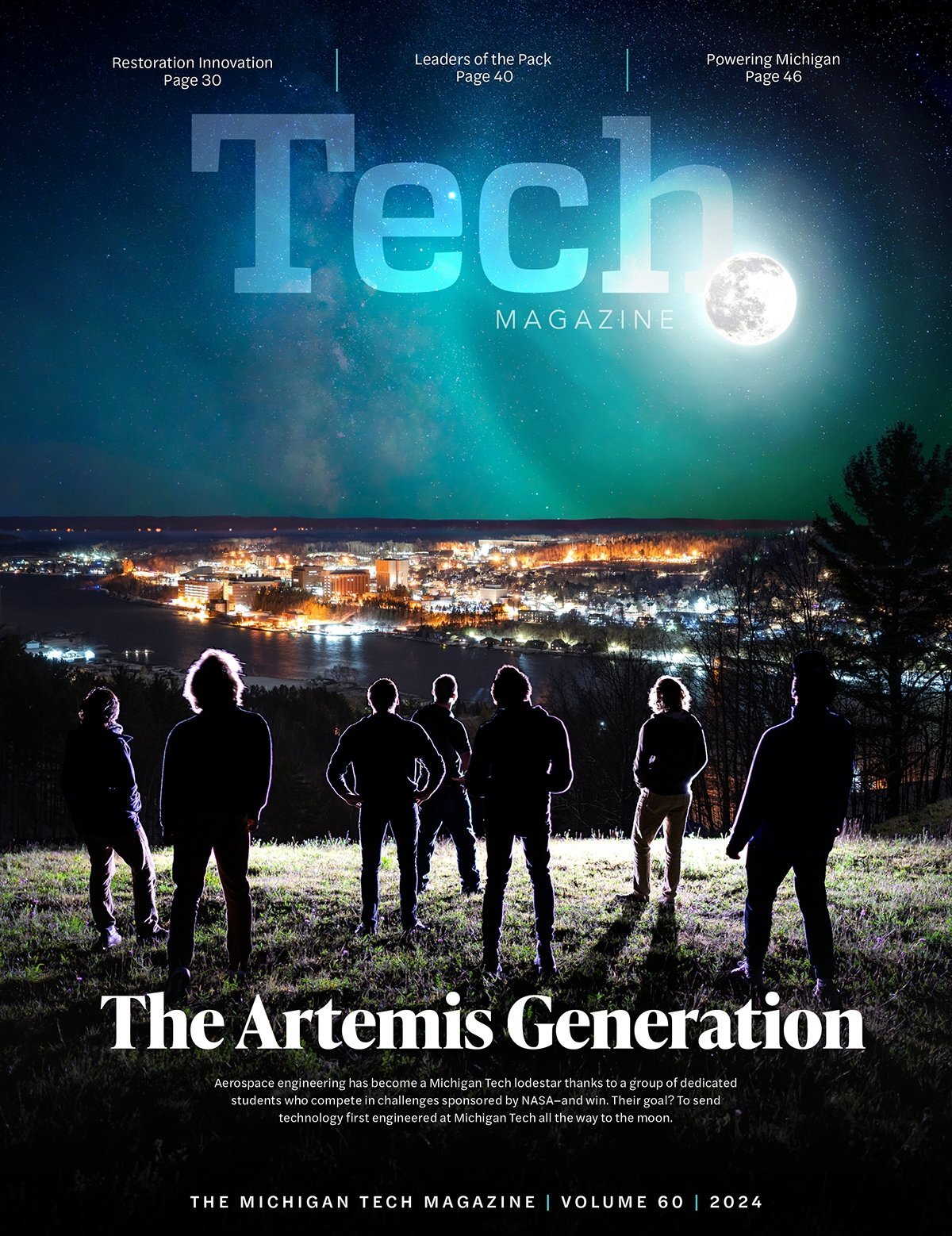

On the cover: Michigan Tech's RV Soliton (foreground) and Ocean Infinity's Armada 8 autonomous surface vessel begin their five-day lake bed mapping mission.

Published by University Marketing and Communications

- Editor

Rick White - Assistant Editor

Jessie Tobias - Writers

Wes Frahm

Hailey Hart '14

Calvin Larson '10

Cyndi Perkins '22 - Art Director

Phoebe Meston - Designers

Bob Gross

Jen Withers - Photographer

Kaden Staley - Videographer

Ben Jaszczak '15 - Production Manager

Jodi Miller - Social Media Manager

Haley Goodreau - Web Editor

Megan Ross '00 - Contributors

Conlan Houston '26, Stanislaw Ryt, Daniel Staelgraeve '26 - Executive Editors

- Andrew Barnard '02 '04, Vice President for Research

- Jessica Brassard '05, Director of Research Development and Communication

- Allison Carter '95, Executive Director of Marketing, University Marketing and Communications

- Natasha Chopp '06 '15 '17, Director of Research Operations and Faculty Liaison

- Rick Koubek, President

- John Lehman, Vice President for University Relations and Enrollment

- Jennifer Lucas '09, Assistant Vice President of Advancement and Alumni Engagement

- Ian Repp, Associate Vice President for University Marketing and Communications

- Bill Roberts, Vice President for Advancement and Alumni Engagement

- Comments to the editor:

magazine@mtu.edu - Research questions:

research@mtu.edu - Alumni inquiries and mailing address changes:

alumni@mtu.edu